Graduate or not?

November 25, 2025

If one word could define Bangladesh’s economic growth story since independence, it would be ‘resilience.’ From natural catastrophes to political turbulence, the country has experienced it all. Yet its economy has consistently managed to bounce back.

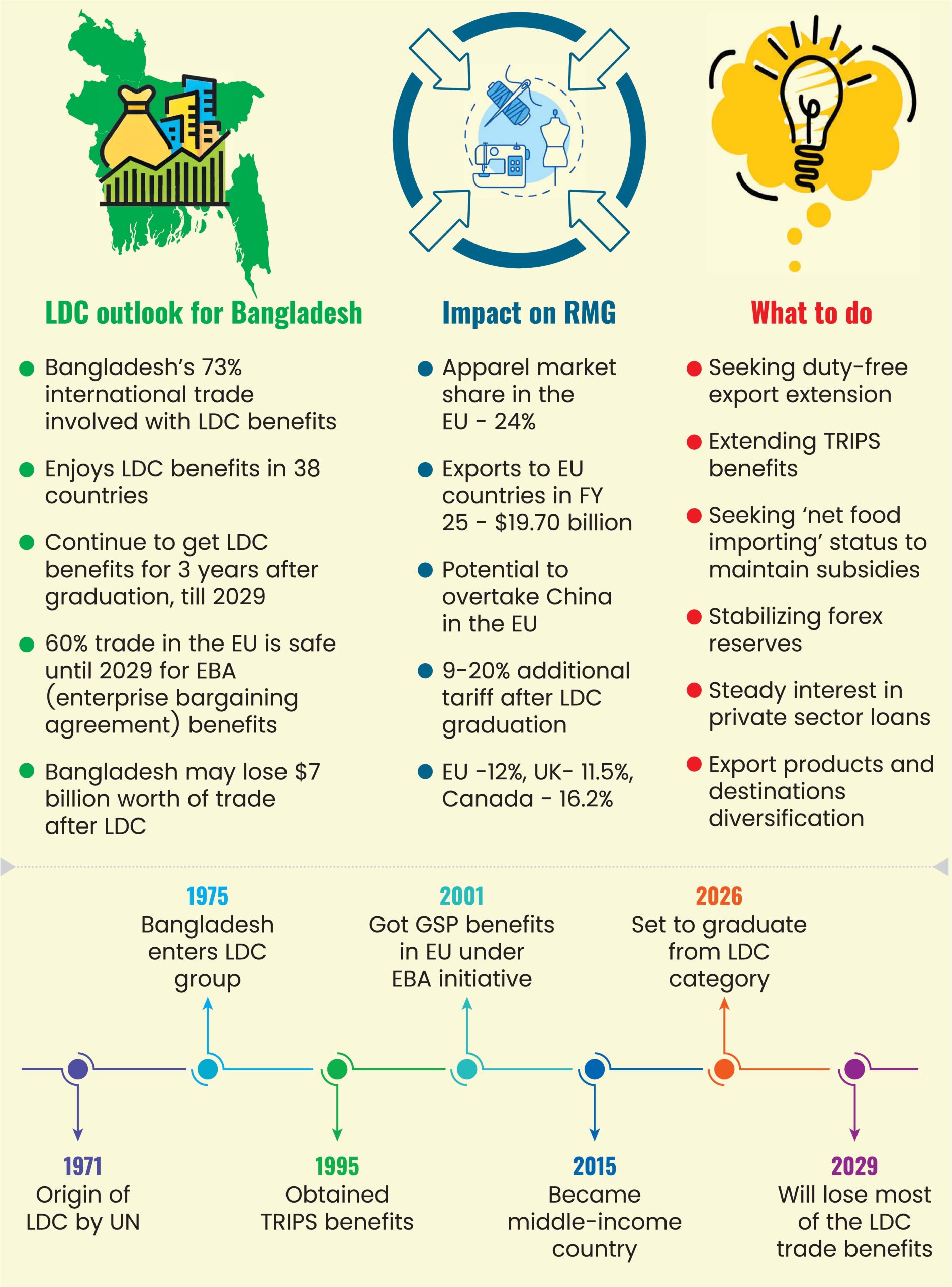

Bangladesh is set to graduate from the group of Least Developed Countries (LDCs) next year, celebrating its hard-won progress in economic growth, poverty reduction, and human development index.

The private sector has been the backbone of the country’s journey to this historical feat. However, the LDC graduation will come with a fair share of challenges.

Finance Adviser Salehuddin Ahmed recently urged the private sector to prepare for a more competitive global environment after graduation while speaking at the 23rd Bangladesh Business Awards program at Radisson Blu Water Garden Hotel.

But earlier this year, during a discussion at the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DCCI) auditorium, the private sector stakeholders called on the government to delay the graduation by at least two to three years, citing prevailing global and local economic challenges.

What are the concerns?

LDC graduation is based on three components: Gross National Income (GNI), the Human Asset Index (HAI), and the Economic Vulnerability Index (EVI). Although Bangladesh has made satisfactory progress in GNI and HAI for graduation, its economic resilience and capacity to absorb external shocks are currently doubted by many.

Shams Mahmud, president of the Bangladesh Thai Chamber of Commerce and Industry (BTCCI), believes that Bangladesh is not yet prepared for a smooth transition, at least in terms of the Economic Vulnerability Index.

“The White Paper on the financial sector clearly states that the past 16 years have left the financial sector in ruins. We have now just started the process of rebuilding. For a smooth transition, the financial sector needs to have fundamental strength, which is not the current scenario,” he told Industry Insider.

“Though panic in the banking sector has subsided, it will take a couple of years to become fully stable. The stock market is more or less stagnant and does not fit into the natural answer for raising alternative financing, as the sector itself is going through a reform process that will take years,” he added.

DCCI President Taskeen Ahmed cited (at a DCCI discussion) various challenges the country is facing right now. He pointed to the severe energy shortage in industries, high inflation, high import duties, high interest rates, complex banking procedures, and limited access to credit for the private sector.

Bangladesh’s economic growth is also at a slow pace. GDP grew only 1.8% in the first quarter of this fiscal year, while the manufacturing sector grew just 1.43%.

Ahmed outlined key priorities for implementing the smooth transition strategy (STS), including the need for a strong leadership framework, policy integration, trade agreements, and financial support mechanisms.

He also emphasized developing skills in the SME sector, securing long-term low-cost credit, signing free trade agreements to boost exports to the Middle East and South Asia, improving infrastructure to attract FDI, and revising revenue and related policies.

Bangladesh is set to hold an election in February 2026. A new political government will take over and need time to settle in and formulate its plan of action. Given the country’s recent turmoil, it will also need time to align the bureaucracy to implement its vision. This alone leaves little time to tackle all these challenges.

“The toughest part to ensure a smooth LDC graduation is preparing Bangladesh’s civil service to facilitate it,” noted Mr. Mahmud.

“We still face the same hurdles and dismissive attitudes whenever questions are raised. This will be a herculean task. Unfortunately, it may become the biggest barrier, as they need to act quickly to solve problems rather than forming one committee and ten subcommittees to examine every issue.”

Emerging challenges

The biggest challenge Bangladesh will face after LDC graduation is the loss of preferential trade benefits, particularly duty-free and quota-free access to major markets such as the European Union, Canada, and Australia.

Currently, about 73% of Bangladesh’s total exports enjoy duty-free benefits, which will no longer be available once graduated. Once they are withdrawn, sectors such as ready-made garments will be significantly impacted, as higher tariffs will reduce competitiveness against rivals like Vietnam and Cambodia.

Another challenge is losing certain subsidies and concessional loans, which may increase the cost of doing business. The private sector will also face stricter rules on labor rights, environmental sustainability, and intellectual property, as global buyers demand higher standards.

“The RMG sector has been the backbone of our economy. However, low-cost financing will not be available in the future. How will the industry find sustainable low-cost financing for investment in new technology and net neutrality, along with circularity directives of the EU, which constitutes roughly 50% of our export market?” Shams Mahmud pointed out the financing issue.

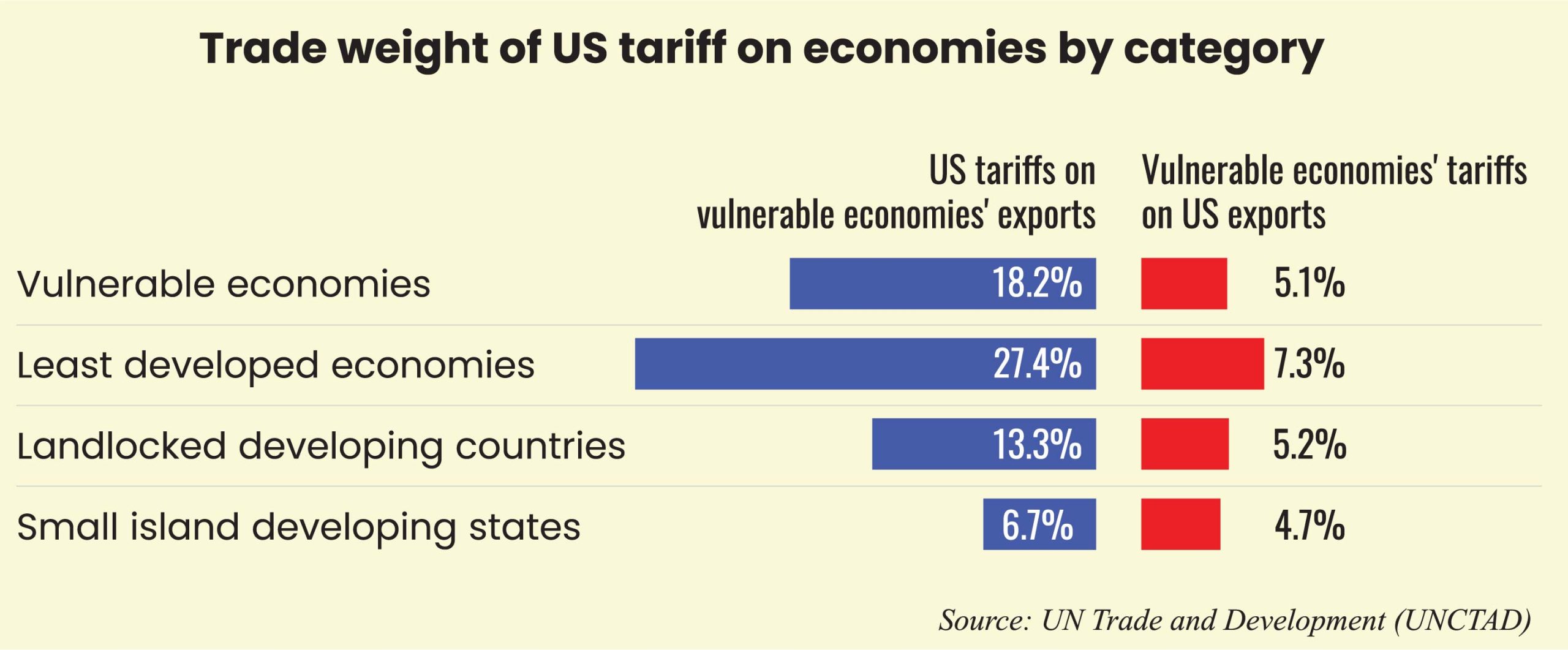

“With Trump’s tariffs, global inflation, rising RMG production worldwide, and weak demand, Bangladesh will face tough times. After LDC graduation, we’ll lose our GSP status and need to shift to GSP Plus, a more complex process. Where will the funding for this transition come from?”

The lack of export diversification remains a major challenge. Bangladesh lacks investment in innovation and technology to stay competitive. Limited research and development, infrastructure bottlenecks, and skill gaps in the workforce are also significant concerns.

According to Dr. M Masrur Reaz, chairman of Policy Exchange Bangladesh, if Bangladesh graduates next year, it’ll pose a challenge to the larger part of RMG exports that are not yet competitive. Other sectors are not competitive at all.

“The export sector has not been diversified. We have long discussed several high-priority sectors, but unfortunately, their global competitiveness has not yet developed. There are various reasons for this, like weaknesses in the business and trade environment as well as sector-level weaknesses,” Dr. Reaz told the author.

However, even some garment products may not remain competitive in the European market. The export volume of ready-made garments is much higher there than in the US, and the product variety is also greater.

“A key challenge after graduation will be the increase in tariffs, but there is something more that is not directly linked to graduation. The EU has made its compliance requirements on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) issues much stricter, and Bangladesh is not yet in a position to fully comply with them,” Dr. Reaz noted.

What’s holding it back, and what needs to be done

Assuming the private sector is not yet prepared for LDC graduation, it must address a fundamental question: ‘How long will it take to prepare, and what is the roadmap?’

Dr. Reaz explicitly put it, “Instead of broadly requesting deferral in graduation, the private sector should present data and evidence-based analysis on why they are not ready and how much time they need. Otherwise, the government and even the United Nations may deny.”

However, private sector stakeholders feel excluded from discussions about LDC graduation readiness.

“A large part of the private sector feels that they were not given enough opportunity to provide input. They were consulted only on a milestone basis, but their active input was not sought. That is why, in reality, no reform implementations have taken place,” Dr Reaz said.

Commerce Secretary Mahbubur Rahman admitted this in the DCCI discussion earlier. He said that initial planning for LDC graduation was inadequate and stressed the need for greater involvement of the private sector.

“The government needs to sharpen its antennas; in other words, it must develop a better understanding of what is happening in both the international and domestic economy. To do this, it must engage in regular consultations with the private sector,” said economist Dr. Syed Akhtar Mahmood, former lead private sector specialist at the World Bank Group.

Interestingly, Bangladesh became eligible for LDC graduation in 2021 and was expected to graduate in 2024. But due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was extended for two years to 2026.

Dr. Reaz argued that it was a comfortable preparatory time period, but we failed to utilize it.

“We got nearly five years. Ideally, this should have been used for necessary improvements in capacity, competitiveness, and policy—a good and comfortable time span. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen any effective effort from the government’s end. It was mostly in ‘grandstanding political celebration’ mode,” he said.

Dr. Mahmood emphasized the fact that we lack the necessary data to see the whole picture of the private sector.

“Especially in the garment industry, or in others as well, we don’t really know what the actual level of productivity is, or what the pattern of productivity looks like. Despite being such a huge industry, the world’s second or third largest exporter, we don’t have live data on its productivity levels or efficiency levels,” he explained.

Not all firms are in the same condition. Many are market leaders—stable and ready for graduation. Dr. Mahmood suggested taking such firms as case studies and applying their models to other firms.

“The government and industry associations have responsibilities here: to collect necessary data, engage experts who can analyze it, carry out benchmarking, and then examine why some firms are performing well while others are not.”

Apart from this, he noted that the country’s investment climate and business environment are also topics of constant discussion.

“This is a significant barrier to private sector growth. The biggest challenge here is policy uncertainty, meaning inconsistency in policies, which reduces investors’ confidence,” he noted.

According to Shams Mahmud, the most important weakness is the absence of import-substituting policies. Such policies take years to show results and require time for industries to become resilient and competitive.

He cited cases in Solomon Islands, Angola, Nepal, and Myanmar, which successfully deferred their graduation due to unique circumstances.

“With the current situation and the upcoming elections, Bangladesh has a strong case for seeking a deferral to ensure a smooth transition. Ignoring this reality makes the road ahead seem fragile and uncertain,” he said.

Dr. Mahmood believes that if graduation is deferred, we must ensure that the extended time is not wasted.

For this, it is necessary to understand the real scenario based on accurate data. The government then needs to engage in effective dialogue with the private sector to design policies that address these challenges.

“Because, if graduation is deferred, the private sector might slow down again—the way students procrastinate once exams are postponed, only to feel the pressure right before the exam!” he concluded.

Ariful Hasan Shuvo is a researcher and journalist based in Dhaka. He is currently working at one of the leading national dailies in Bangladesh, where he crafts analyses and stories on various development issues to influence policymaking. He is passionate about development economics and seeks to understand why nations struggle to overcome poverty, unemployment, and inequality. He dreams of a world free of those.

Most Read

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

How AI is fast-tracking biotech breakthroughs

Starlink, satellites, and the internet

What lack of vision and sustainable planning can do to a city

A nation in decline

Does a tourism ban work?

Case study: The Canadian model of government-funded healthcare

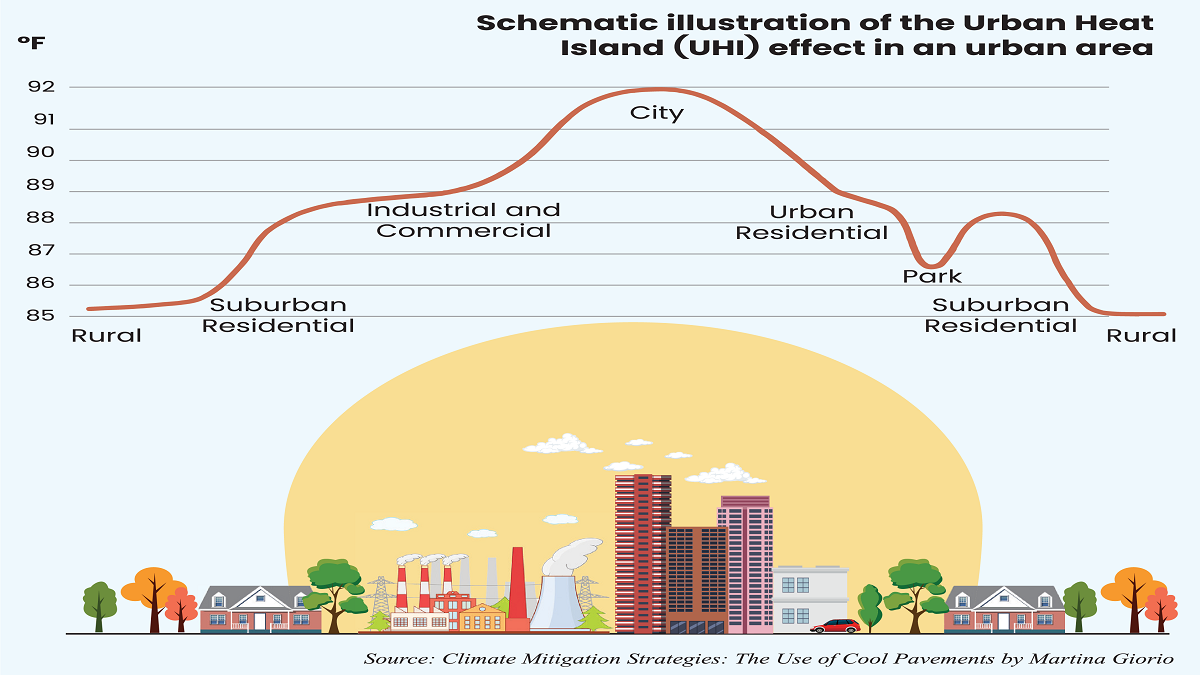

A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

You May Also Like